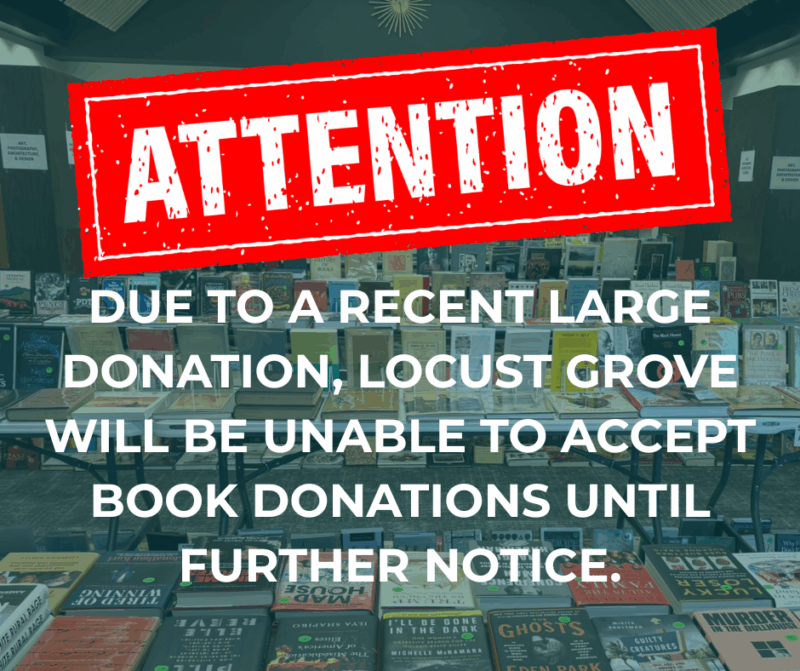

Lewis and Clark

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark visited Locust Grove together on November 8, 1806 upon returning from their historic expedition to the Pacific.

“Captains Lewis & Clark arrived at the Falls on their return from the Pacific Ocean after an absence of a little more than three years”

Johnathan Clark’s Diary, November 5th, 1806

A Stopping Place for Lewis and Clark

Locust Grove is the only verified remaining structure west of the Appalachian Mountains known as a stopping point for Lewis and Clark. It was here that people at the Falls would have had perhaps the first opportunity to learn about what remains the greatest exploration venture in our county’s history.

George Rogers Clark, older brother to William Clark, spent the last nine years of his life at Locust Grove, from 1809 until his death in 1818.

General William Clark, 1770-1838

William Clark, youngest brother of George Rogers Clark and Lucy Clark Croghan, moved from Virginia to Kentucky with his parents in 1784. Beginning in 1789 he served in a number of military expeditions against the native Americans of the developing lands of the backcountry, including missions to contain the Creek and Cherokee nations and expeditions under Generals Scott and Wilkinson against the native Americans on the Wabash. He was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the 4th Sub Legion under General Wayne in March 1793.

Returning to Kentucky in 1796, Clark lived with his parents at their Mulberry Hill farm near Louisville. When they died, he inherited the homestead but sold it to his eldest brother, Jonathan, in 1800 and moved to Clarksville, Indiana, with his brother, George Rogers Clark.

A Presidential Task

In 1803, President Thomas Jefferson commissioned Clark along with Meriwether Lewis to make a western expedition to establish an American presence in the far northwest; to investigate a water passage to the Western Sea; to map and investigate the new Louisiana purchase; to report the culture, commerce, and capabilities of the many native-American tribes of the area; and to observe and collect botanical and biological specimens.

Members of the expedition assembled at Louisville, KY, in October, 1803, and moved on to camp above St. Louis for the winter. Upon reaching the native Mandan villages in present-day South Dakota, they acquired the services of Toussaint Charbonneau, a French trader, and his pregnant 15-year-old Shoshone wife, Sacagewea (Suh-COG-uh-wea), as interpreters.

By June of 1805, Lewis and Clark and their party were at the Great Falls of present-day Montana and made a difficult 10-day portage around it. Obtaining horses from the Shoshones, they crossed the Bitterroot Mountains, went down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean in late November, and wintered at Fort Clatsop, Oregon.

An Astonishing Return

The expedition returned to St. Louis on September 20, 1806, to the astonishment of many who had given them up for dead months before. After disbanding most of the company, Lewis and Clark returned east in October, pausing for three weeks in Louisville and visiting Locust Grove on November 8th. Lewis then moved on to report to the President in Washington City where Clark later Joined him.

Post Expedition Life

After Clark’s marriage in 1808, he was appointed Indian agent at St. Louis. In 1813, he was made Governor of the Missouri Territory. In 1822, President Monroe appointed him Superintendent of Indian Affairs to establish and secure treaties with the western tribes. He died in St. Louis in 1838.

York, ca. 1772 – before 1832

York, born between 1770-1775, most likely in Caroline County Virginia, was enslaved by Jonathan Clark, and then willed to his son William Clark. York became the only enslaved member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition from 1803-1806, becoming the first African American to cross the United States coast to coast. York’s upbringing was alongside Clark, as they were very near in age. York moved with the Clark Family to Kentucky in 1785, living and working at the family farm called “Mulberry Hill.”

In October of 1803 York was in attendance with the explorers leaving the Falls of the Ohio, headed westward. York became an invaluable member of the expedition, particularly in diplomatic relations with the many Indigenous Tribes the group met along the way. York was allowed to voice his vote along with the other men concerning decisions such as where to make campsites, and which direction to head next. However, while granted this agency during the expedition, upon his return with the Corps, he was not granted his freedom from enslavement by Clark.

Clark and York’s relationship soured when Clark moved to St. Louis and took York with him, away from his wife and community. Eventually, York was hired out to a man in Louisville, so he could be nearer to his family. Sometime between 1815 and 1832 Clark manumitted York, but the documentation has not yet been discovered. The date and place of York’s death remains unknown.

Meriwether Lewis, 1774-1809

Meriwether Lewis, born in Virginia in 1774, was one of the titular leaders of the Corps of Discovery alongside William Clark. Lewis had a formal education from Liberty Hall, now Washington and Lee University, and had served in the state militia and as a captain in the army. Setting off from St. Louis in 1804, the Corps of Discovery faced numerous challenges. Along the way, Lewis kept a detailed journal and collected samples of plants and animals encountered along the way.