Wash House

Originally a fixture of the house proper, many country and town houses in England and America used a room dedicated to fabric cleaning. Over the course of the eighteenth century, washrooms underwent a relocation to a separate one-bedroom structure in elite households, such as would have been the case in Locust Grove, the hearth of which would have been dedicated for both laundry and cooking. Requiring total cleanliness, the washroom ultimately moved to an individual building independently of the kitchen, now collectively referred to both a “wash house” or a “laundry” (both terms were common practice in the eighteenth century).

While this may seem like a small space, wash house size did not stem from family size, but from the number of linens and other textiles the family purchased and utilized as well as the number of workers that would be laboring in them. Also, during months with warmer weather laundry work was often extended to the outdoor spaces as well for both washing and drying of textiles.

Enslaved women would have been tasked with the completion of the laundry and they held a wide breadth of knowledge of laundry, washing, scouring, mending, needlework, embroidery, lace making, darning, and other handicraft dealing with textiles.

Laundry was a physically and mentally daunting task, with enslaved women suffering from scarring and burning of their hands and arms as a result of working with the lye used in soap, boiling washing water, hot irons, and other solvents that were used when tackling laundry during this time period.

Laundry would begin by mending any rips or tears and tending to any missing buttons. Enslaved children would often help bring the firewood and water to the laundry, and between 20-25 gallons of water were needed for just one “load” (washtub full) of laundry. Clothes would first soak in a washtub for a day or

two, and stains were scrubbed by various different methods depending on cause/type of stain. After this clothing would be moved to a larger copper boiler and soap added. (Note: different fabrics had different treatments.)

Once laundry was washed and boiled, the laundress would then pick the clothes out of the tubes with sticks and beat them with flat bats (called a battledore) against a wooden battling block or bench to remove

dirt. The clothes would then be boiled again to rid the garments of any lice or fleas, and rinsed with hot water then cold water. Laundry would then be hung on racks or ropes near the fire or outside in the sun for air drying. Once dry, textiles would be ironed, folded, and stored until ready for their next use.

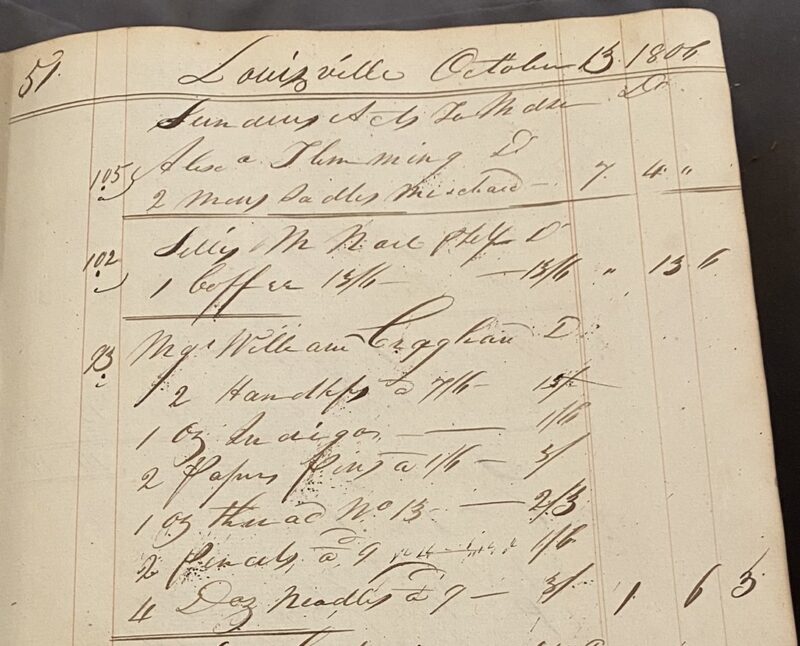

Maj. William Croghan frequently purchased items from local merchants Fitzhugh & Rose. The most common items for the wash house were:

- Handkerchiefs

- Indigo

- Pins

- Thread

- Needles

This image, from the Fitzhugh and Rose ledgers at the Filson Historical Society, show some of those purchases from October 1808.